So far we have used the integral mainly to to compute areas of plane regions. It turns out that the definite integral can also be used to calculate the volumes of certain types of three-dimensional solids. The class of solids we will consider in this lab are called Solids of Revolution because they can be obtained by revolving a plane region about an axis.

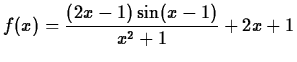

As a simple example, consider the graph of the function ![]() for

for

![]() , which appears below.

, which appears below.

![\includegraphics[height=2.0in,width=4.0in]{volrev_fig1new.ps}](img15.png)

If we take the region between the graph and the x-axis and revolve it about the x-axis, we obtain the solid pictured in the next graph.

![\includegraphics[height=2.5in,width=4in]{volrev_fig2new.ps}](img16.png)

To help you in plotting surfaces of revolution, A

Maple procedure called revolve has been written. The

commands used to produce the graphs are shown below.

The revolve procedure, as well

as the RevInt, LeftInt, and

LeftDisk procedures described below are all part of the CalcP package, which must be loaded first. The last line in the

example below shows the

optional argument for revolving the graph of ![]() about the line

about the line

![]() instead of the default

instead of the default ![]() .

.

> with(CalcP7): > f := x -> x^2+1; > plot(f(x),x=-2..2); > revolve(f(x),x=-2..2); > revolve(f(x),x=-2..2,y=-2)

The revolve command has other options that you should read about in the help screen. For example, you can speed the command up by only plotting the surface generated by revolving the curve with the nocap argument, and you can also plot a solid of revolution formed by revolving the area between two functions. Try the following examples. (Note: The last example shows how to use revolve with a function defined piecewise using the piecewise command.)

> revolve({f(x),0.5},x=-2..2,y=-1);

> revolve(cos(x),x=0..4*Pi,y=-2,nocap);

> revolve({5,x^2+1},x=-2..2);

> g := x -> piecewise(x<0,-x+1/2,x^2-x+1/2);

> revolve(g(x),x=-1..2);

It turns out that the volume of the solid obtained by revolving the

region between the graph and the ![]() -axis

about the

-axis

about the ![]() -axis can

be determined from the integral

-axis can

be determined from the integral

Where does this formula come from? To help you understand it, Two more Maple procedures, RevInt and LeftDisk, have been written. The procedure RevInt sets up the integral for the volume of a solid of revolution, as shown below. The Maple commands evalf and value can be used to obtain a numerical or analytical value.

> RevInt(f(x),x=-2..2); > value(RevInt(f(x),x=-2..2)); > evalf(RevInt(f(x),x=-2..2));

The integral formula given above for the volume of a solid of

revolution comes, as usual, from a limit process. Recall the

rectangular approximations we used for plane regions. If you think of

taking one of the rectangles and revolving it about the x-axis, you

get a disk whose radius is the height ![]() of the rectangle and

thickness is

of the rectangle and

thickness is ![]() , the width of the rectangle. The volume of

this disk is

, the width of the rectangle. The volume of

this disk is

![]() . If you revolve all of the rectangles in

the rectangular approximation about the x-axis, you get a solid made

up of disks that approximates the volume of the solid of revolution

obtained by revolving the plane region about the x-axis.

. If you revolve all of the rectangles in

the rectangular approximation about the x-axis, you get a solid made

up of disks that approximates the volume of the solid of revolution

obtained by revolving the plane region about the x-axis.

To help you visualize this approximation of the volume by disks, the LeftDisk procedure has been written. The syntax for this procedure is similar to that for revolve, except that the number of subintervals must be specified. The examples below produce approximations with five and ten disks. The latter approximation is shown in the graph below.

> LeftDisk(f(x),x=-2..2,5); > LeftDisk(f(x),x=-2..2,10); > LeftInt(f(x),x=-2..2,5); > LeftInt(f(x),x=-2..2,10);

The two LeftInt commands above add up the volumes in the disk approximations of the solid of revolution.

![\includegraphics[height=2.5in,width=4in]{volrev_fig3new.ps}](img17.png)

> f:= x-> sqrt(x) +1; > vol:= int(Pi*f(x)^2, x=0..9); > evalf(vol);

over the interval

over the interval

.

.

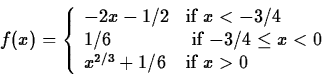

> f := x -> piecewise(x<-3/4,-2*x-1/2,x<0,1/6,x^(2/3)+1/6);

Plot this function (without revolving it) over the interval

![]() and identify the formula for each part of the

graph. Then, revolve this function about the

and identify the formula for each part of the

graph. Then, revolve this function about the ![]() axis over the

same interval and comment on the glass Kevin and Jim

designed. Finally, compute the volume of the part of this glass that

could be filled with liquid, assuming the stem is solid. (Hint - your

integral will involve only one of the formulas used to define the

function.)

axis over the

same interval and comment on the glass Kevin and Jim

designed. Finally, compute the volume of the part of this glass that

could be filled with liquid, assuming the stem is solid. (Hint - your

integral will involve only one of the formulas used to define the

function.)