For symmetric objects, the balance point or center of mass is usually easy to find. For example, the balance point of an empty see-saw is the exact center. Similarly, the balance points for rectangles or circles are just the geometrical centers. For non-symmetric objects, the answer is not so clear, but it turns out that there is a fairly simple algorithm involving integrals for determining balance points.

We begin by restricting our attention to thin plates of uniform

density. In Engineering and Science, this type of object is called a

lamina. For mathematical purposes, we assume that the lamina is

bounded by ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , with

, with

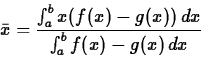

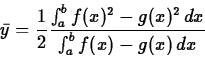

![]() . Then the book gives the following formulas for the coordinates

. Then the book gives the following formulas for the coordinates

![]() of the center of mass.

of the center of mass.

> f := x-> -x^2+4*x+6;

> g := x-> x/3+2;

> plot({f(x),g(x)},x=-2..6);

> a := fsolve(f(x)=g(x),x=-2..0);

> b := fsolve(f(x)=g(x),x=4..6);

> mass:=int(f(x)-g(x),x=a..b);

We will call the integral mass instead of area and will use it in the coordinate formulas. Using labels can help you organize your calculations and avoid

mistakes. Computing the mass separately also lets you check it. If you

get a negative value for the mass, something is wrong and you have to

check what you have done. A common mistake is reversing the order of

the functions.

> xbar := int(x*(f(x)-g(x)),x=a..b)/mass; > ybar := 1/2*int(f(x)^2-g(x)^2,x=a..b)/mass;To check if the answer is reasonable you may plot the point.

> plot([f(x), g(x), [[xbar, ybar]]], x = -2 .. 6, style = [line, line, point], color = black,symbolsize=30);