One of the basic useful principles of analyzing distributed forces is

the idea of replacing them with a single, aggregate force ![]() that acts at a single point and is somehow equivalent to the original

distributed force. This may not always be possible, but this technique

has found great use in engineering and science. As a simple example,

suppose we have gravity acting on a solid plate of uniform thickness and

density, but

irregular shape. Finding the equivalent force is really the problem of

finding the point where we could exactly balance the plate. This

balance point is often called the center of mass of the body.

that acts at a single point and is somehow equivalent to the original

distributed force. This may not always be possible, but this technique

has found great use in engineering and science. As a simple example,

suppose we have gravity acting on a solid plate of uniform thickness and

density, but

irregular shape. Finding the equivalent force is really the problem of

finding the point where we could exactly balance the plate. This

balance point is often called the center of mass of the body.

For symmetric objects, the balance point is usually easy to find. For example, the balance point of an empty see-saw is the exact center. Similarly, the balance points for rectangles or circles are just the geometrical centers. For non-symmetric objects, the answer is not so clear, but it turns out that there is a fairly simple algorithm involving integrals for determining balance points.

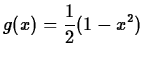

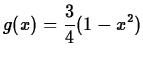

We begin by restricting our attention to thin plates of uniform

density. In Engineering and Science, this type of object is called a

lamina. For mathematical purposes, we assume that the lamina is

bounded by ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , with

, with

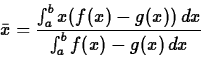

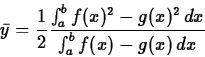

![]() . Then the book gives the following formulas for the coordinates

. Then the book gives the following formulas for the coordinates

![]() of the center of mass.

of the center of mass.

> f := x -> x^3-3*x^2-x+3; > g := x -> 3-x;Next you need to find the intersection of the two functions. These intersection points will be used as the limits of intgration.

> solve(f(x)=g(x),x);

> plot({g(x),f(x)},x=0..3);

Notice that the graph of Now we are ready to compute the center of mass. Using labels, as shown below, can help you organize your calculations and avoid mistakes. Computing the mass separately also lets you check it. If you get a negative value for the mass, something is wrong and you have to check what you have done. A common mistake is reversing the order of the functions.

> mass := int(g(x)-f(x),x=0..3); > x_bar := int(x*(g(x)-f(x)),x=0..3)/mass; > y_bar := 1/2*int(g(x)^2-f(x)^2,x=0..3)/mass;

.

.

.

.