Next: About this document ...

Up: lab_template

Previous: lab_template

Subsections

The purpose of this lab is to introduce you to curve computations

using Maple for parametric curves and vector-valued functions in three

dimensions.

To assist you, there is a worksheet associated with this lab that

contains examples. You can

copy that worksheet to your home directory with the following command,

which must be run in a terminal window, not in Maple.

cp ~bfarr/Curves3D_start.mws ~

You can copy the worksheet now, but you should read through the lab

before you load it into Maple. Once you have read to the exercises,

start up Maple, load

the worksheet Curves3D_start.mws, and go through it

carefully. Then you can start working on the exercises

A parametric curve in three dimensions is a triple of functions

,

,  ,

,  for

for  in some interval

in some interval  .

A vector-valued function in

three dimensions is a function

.

A vector-valued function in

three dimensions is a function  that associates a vector in

the plane with

each value of

that associates a vector in

the plane with

each value of  in its domain. Such a vector valued function can

always be

written in component form as follows,

in its domain. Such a vector valued function can

always be

written in component form as follows,

where  ,

,  , and

, and  are functions defined on some interval

are functions defined on some interval  . From our

definition of a parametric curve, it should be clear that you can

always associate a

parametric curve with a vector-valued function by just considering the

curve traced out by the head of the vector. However, there are

lots of situations where a vector-valued function is more

appropriate. We will focus on

the case of motion of a particle in three dimensions. That is, we have a

vector-valued function

. From our

definition of a parametric curve, it should be clear that you can

always associate a

parametric curve with a vector-valued function by just considering the

curve traced out by the head of the vector. However, there are

lots of situations where a vector-valued function is more

appropriate. We will focus on

the case of motion of a particle in three dimensions. That is, we have a

vector-valued function  that gives the position at time

that gives the position at time

of a moving point

of a moving point  . The velocity of this point is

given by the derivative

. The velocity of this point is

given by the derivative

and the acceleration is given

by the second derivative,

and the acceleration is given

by the second derivative,

. If the velocity,

. If the velocity,

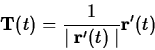

, is never zero, then we can define the unit tangent

vector

, is never zero, then we can define the unit tangent

vector  and the curvature

and the curvature  the same way we

did in two dimensions by

the same way we

did in two dimensions by

and

If the curvature is never zero for a particular curve, then we can

define another intrinsic property of curve, the unit normal vector

by the following equation.

by the following equation.

It can be shown that at each point on the curve the vector  defined

by this equation is a unit vector that is always perpendicular to the

tangent vector

defined

by this equation is a unit vector that is always perpendicular to the

tangent vector  at that point. Furthermore, the unit normal vector

at that point. Furthermore, the unit normal vector

always points in the direction of the centripetal

acceleration required to keep a particle moving on the curve. One way

to see this is to compute the acceleration by differentiating both

sides of the equation

always points in the direction of the centripetal

acceleration required to keep a particle moving on the curve. One way

to see this is to compute the acceleration by differentiating both

sides of the equation

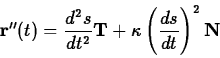

Using the chain rule and the definition of the

curvature and the normal vector one obtains the following important

equation.

To see why this equation is useful, recall that  is the

speed, so

is the

speed, so  is the rate of change of the speed.

That is, this term measures whether the particle is speeding up or

slowing down. Because this component of the

acceleration is in the direction of the tangent vector it is often

called the tangential acceleration, denoted by the symbol

is the rate of change of the speed.

That is, this term measures whether the particle is speeding up or

slowing down. Because this component of the

acceleration is in the direction of the tangent vector it is often

called the tangential acceleration, denoted by the symbol  . The

component of the acceleration in the direction of the normal vector is

called the normal acceleration, denoted

. The

component of the acceleration in the direction of the normal vector is

called the normal acceleration, denoted  . In the case of motion

on a circular path, the curvature is the reciprocal of the radius, so

this term should be easily recognizable as the centripetal

acceleration.

. In the case of motion

on a circular path, the curvature is the reciprocal of the radius, so

this term should be easily recognizable as the centripetal

acceleration.

Computing these quantities is generally not an

easy task. The Getting started worksheet for this lab

describes commands from the CalcP package that simplify these

calculations and provides examples for you to work from.

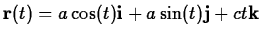

- As described in the text, a curve of the form

is called a circular

helix. It has the properties that the speed, curvature and normal and

tangential acceleration are all constant. Consider the vector-valued

function

is called a circular

helix. It has the properties that the speed, curvature and normal and

tangential acceleration are all constant. Consider the vector-valued

function

.

.

- Plot the graph of this function for

. Explain why the graph might be called an elliptical helix. (Note

- the plot you get might make it look like a circular helix, that is

one whose projection in the

. Explain why the graph might be called an elliptical helix. (Note

- the plot you get might make it look like a circular helix, that is

one whose projection in the  plane is a circle, because of the

way Maple will scale the axes. The best way to overcome this is to

use the optional argument view. For example, try adding

plane is a circle, because of the

way Maple will scale the axes. The best way to overcome this is to

use the optional argument view. For example, try adding

view=[-3..3,-3..3,0..2*Pi]

to your VPlot command.)

- Plot the speed for

. Is it constant?

. Is it constant?

- Plot the curvature for

. Is it constant?

. Is it constant?

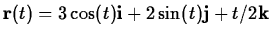

- In the old days, students at WPI used to do projects in calculus

as well as labs. One such project called for students to design a loop for a

roller coaster. A group from the class of `95 came up with the

following design, which they called the ``Vomit Comet''.

Here  is the position in units of meters of the car on the loop

and

is the position in units of meters of the car on the loop

and  is the time in seconds.

is the time in seconds.

- Plot the position for

. The best way to view

the loop is probably looking in along the

. The best way to view

the loop is probably looking in along the  axis. How high

(approximately) is the top of the loop, in meters?

axis. How high

(approximately) is the top of the loop, in meters?

- Find the speed of the car and convert it to units of miles per

hour ( 1 meter per second is about 2.24 miles per hour). Does it seem

reasonable for a roller coaster?

- Plot the curvature of the loop for

.

.

- What is the radius of curvature of the loop at

? At

? At  ?

?

- Plot the normal acceleration of the loop for

. To put it in perspective, you might want to plot the normal

acceleration divided by

. To put it in perspective, you might want to plot the normal

acceleration divided by  , the acceleration due to gravity in

units of meters per second squared.

, the acceleration due to gravity in

units of meters per second squared.

- Based on your results, do you think the loop lives up to its name?

Next: About this document ...

Up: lab_template

Previous: lab_template

William W. Farr

2003-01-20

![]() by the following equation.

by the following equation.