Next: About this document ...

Up: lab_template

Previous: lab_template

Subsections

The purpose of this lab is to introduce you to curve computations

using Maple for parametric curves and vector-valued functions in the

plane.

To assist you, there is a worksheet associated with this lab that

contains examples and even solutions to some of the exercises. You can

copy that worksheet to your home directory with the following command,

which must be run in a terminal window, not in Maple.

cp ~bfarr/Curves2D_start.mws ~

You can copy the worksheet now, but you should read through the lab

before you load it into Maple. Once you have read to the exercises,

start up Maple, load

the worksheet Vec2D_start.mws, and go through it

carefully. Then you can start working on the exercises.

By parametric curve in the plane, we mean a pair of equations  and

and  for

for  in some interval

in some interval  . A vector-valued function in

the plane is a function

. A vector-valued function in

the plane is a function  that associates a vector in

the plane with

each value of

that associates a vector in

the plane with

each value of  in its domain. Such a vector valued function can

always be

written in component form as follows,

in its domain. Such a vector valued function can

always be

written in component form as follows,

where  and

and  are functions defined on some interval

are functions defined on some interval  . From our

definition of a parametric curve, it should be clear that you can

always associate a

parametric curve with a vector-valued function by just considering the

curve traced out by the head of the vector.

. From our

definition of a parametric curve, it should be clear that you can

always associate a

parametric curve with a vector-valued function by just considering the

curve traced out by the head of the vector.

For this lab, we will assume that we have a

vector-valued function  that gives the position at time

that gives the position at time

of a moving point

of a moving point  in the plane. The velocity of this point is

given by the derivative

in the plane. The velocity of this point is

given by the derivative

and the acceleration is given

by the second derivative,

and the acceleration is given

by the second derivative,

.

In many applications of

curvilinear motion, we need to know the magnitude of the velocity, or

the speed. This is easy to compute - just take the magnitude

.

In many applications of

curvilinear motion, we need to know the magnitude of the velocity, or

the speed. This is easy to compute - just take the magnitude

. If you think of the speed as the rate of change

of distance along the curve, and recall that arc length is distance

measured along the curve, then you have the following interpretation

of the speed

. If you think of the speed as the rate of change

of distance along the curve, and recall that arc length is distance

measured along the curve, then you have the following interpretation

of the speed

where  is arc length.

is arc length.

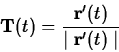

If the speed is not zero for any value of  in the interval

in the interval  ,

then it is possible to define a unit vector,

,

then it is possible to define a unit vector,  that is

tangent to the curve as follows.

that is

tangent to the curve as follows.

Using this definition, you can write the velocity in the following form.

This is not the most useful form for calculating the velocity, but it

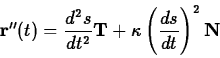

does lead to a useful way of thinking about the acceleration

experience by a particle moving in a curvilinear path.

If the path is a straight line, acceleration depends only on

whether the particle is speeding up or slowing down. In a curve, however,

there is an additional acceleration, called the centripetal

acceleration, that is needed to keep the particle moving on the curve. The

magnitude of this acceleration depends on the speed of the car and how

much the path is curving. It turns out that you can quantify this

with an intrinsic property of the curve called

the curvature, usually denoted  , defined by the following

equation.

, defined by the following

equation.

That is, the curvature is the magnitude of the rate of change of the

tangent vector  with respect to arc length. For example,

the curvature of a straight line is zero and it can be shown that the

curvature of a circle of radius

with respect to arc length. For example,

the curvature of a straight line is zero and it can be shown that the

curvature of a circle of radius  is the same for every point on the

circle and is given by

is the same for every point on the

circle and is given by  .

.

If the curvature is never zero for a particular curve, then we can

define another intrinsic property of curve, the unit normal vector

by the following equation.

by the following equation.

It can be shown that at each point on the curve the vector  defined

by this equation is a unit vector that is always perpendicular to the

tangent vector

defined

by this equation is a unit vector that is always perpendicular to the

tangent vector  at that point. Furthermore, the unit normal vector

at that point. Furthermore, the unit normal vector

always points in the direction of the centripetal

acceleration required to keep a particle moving on the curve. In your

text, the following important relation is derived.

always points in the direction of the centripetal

acceleration required to keep a particle moving on the curve. In your

text, the following important relation is derived.

To see why this equation is useful, recall that  is the

speed, so

is the

speed, so  is the rate of change of the speed.

That is, this term measures whether the particle is speeding up or

slowing down. Because this component of the

acceleration is in the direction of the tangent vector it is often

called the tangential acceleration, denoted by the symbol

is the rate of change of the speed.

That is, this term measures whether the particle is speeding up or

slowing down. Because this component of the

acceleration is in the direction of the tangent vector it is often

called the tangential acceleration, denoted by the symbol  . The

component of the acceleration in the direction of the normal vector is

called the normal acceleration, denoted

. The

component of the acceleration in the direction of the normal vector is

called the normal acceleration, denoted  . In the case of motion

on a circular path, the curvature is the reciprocal of the radius, so

this term should be easily recognizable as the centripetal

acceleration for uniform circular motion.

. In the case of motion

on a circular path, the curvature is the reciprocal of the radius, so

this term should be easily recognizable as the centripetal

acceleration for uniform circular motion.

Computing these quantities is generally not an

easy task. The Getting started worksheet for this lab

describes commands from the CalcP package that simplify these

calculations and provides examples for you to work from.

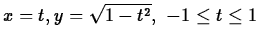

- Consider the parametric curve

,

,  . Plot

the graph of this curve for

. Plot

the graph of this curve for

. Identify the points

for

. Identify the points

for  ,

,  , and

, and  on your graph. Indicate the motion

on the curve as

on your graph. Indicate the motion

on the curve as  increases. This is probably best done by hand on

the printed copy.

increases. This is probably best done by hand on

the printed copy.

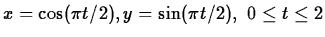

- For each of the following parametric curves, plot the graph and

locate the point on your graph that corresponds to

.

.

-

-

Explain why the graph is the same in each case, even though the

parametrizations are different.

- For following vector function, compute the unit

tangent vector

, the unit normal vector

, the unit normal vector

, the curvature

, the curvature  , and the normal and

tangential accelerations at the indicated value of

, and the normal and

tangential accelerations at the indicated value of  . Include a plot

of the curve for the given

. Include a plot

of the curve for the given  interval in your worksheet.

interval in your worksheet.

Compute  ,

,

,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  at

at

Next: About this document ...

Up: lab_template

Previous: lab_template

William W. Farr

2004-01-16

![]() that gives the position at time

that gives the position at time

![]() of a moving point

of a moving point ![]() in the plane. The velocity of this point is

given by the derivative

in the plane. The velocity of this point is

given by the derivative

![]() and the acceleration is given

by the second derivative,

and the acceleration is given

by the second derivative,

![]() .

In many applications of

curvilinear motion, we need to know the magnitude of the velocity, or

the speed. This is easy to compute - just take the magnitude

.

In many applications of

curvilinear motion, we need to know the magnitude of the velocity, or

the speed. This is easy to compute - just take the magnitude

![]() . If you think of the speed as the rate of change

of distance along the curve, and recall that arc length is distance

measured along the curve, then you have the following interpretation

of the speed

. If you think of the speed as the rate of change

of distance along the curve, and recall that arc length is distance

measured along the curve, then you have the following interpretation

of the speed

![]() in the interval

in the interval ![]() ,

then it is possible to define a unit vector,

,

then it is possible to define a unit vector, ![]() that is

tangent to the curve as follows.

that is

tangent to the curve as follows.

![]() by the following equation.

by the following equation.